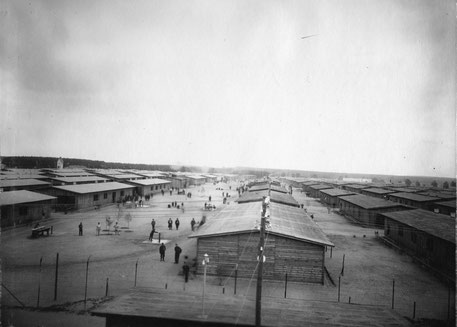

Between December 1917 and January 1918, 2.921 Italian officers and petty officers were imprisoned in Celle-Lager north of Hannover, after the defeat of Caporetto.[1] The experience of these soldiers[2] during those first months of captivity was marked by hunger[3] and deprivation. It is possible to witness its hardship by reading the numerous letters sent to the families.[4]

In this troubling situation, the Arte Culinaria came to light.[5] Searching for a pass-time in those gloomy days in which hunger prevented them from moving, Giuseppe Chioni (Quinto, Genova 1895 – ivi, 1959), second lieutenant of infantry, and Luigi Marrazza (1897, Milano - ?)[6] decided to collect and transcribe recipes reported to them by their prison mates.

What resulted from this work is a hybrid form of text that is as much as a collection of recipes as of memories. Comparing this document to the famous nineteenth-century Italian cookbook La scienza in cucina[7] can help us to gain a more complete image of culinary practice in Italy at the beginning of the twentieth century. The Arte Culinaria captures its inherent variety, a much wider spectrum than the one described by the author of the Scienza Pellegrino Artusi. Home cuisine for these prisoners was a way of remembering one’s identity in a situation of extreme privation and difficulty.

The Arte Culinaria as a cookbook

Although it was never published by the authors, the pages of the Arte Culinaria are carefully bound together. The cookbook was donated to the Archivio Ligure di Scrittura Popolare di Genova by one of the authors’ nieces, Roberta Chioni. The precarious state of the binding caused the loss of some of the pages. The book is a thick notebook, counting around 200 pages (the lines of the pages were hand-drawn). It contains a preface and an index. Each chapter is preceded by very detailed illustrations, which function as frames to the titles of the chapters under which the courses are organized.

Following its structure, we find Starters, Sauces, Soups and Pasta, Pizzas, Fish, Meat and Wildfowl, Omelettes and eggs, Polenta, Bread[8], Vegetables and Legumes and finally Desserts and Marmalade. The 399 recipes provide interesting insights into the diversity of regional Italian cuisine.

This becomes evident when we compare the manuscript with the Italian most famous cookbook La Scienza in cucina (1891)[9] written by Pelegrino Artusi. The two books have very few recipes in common: Artusi’s collection provides recipes from the cuisine of Center and North Italy and disregards polenta in North Italian foodways. Chioni, on the other hand, spends an entire chapter on maize dishes in his Arte Culinaria. He is aware of the major role that this grain played in the dietary memories of his fellow prisoners, who came mostly from northern Italy.

As a result, Arte Culinaria provides a more comprehensive “food geography” of Italy than the one sketched in Artusi’s La scienza in cucina, potentially becoming an important source for reconstructing Italian food history. For instance, the Arte Culinaria features recipes for “Spaghetti alla Catanese”, “Lasagna alla Napoletana”, “Cardoni all'abbruzzese", “Zuppa di polenta alla culunganes”[10] alongside each other, despite their diverse provenance.

The use of the expression “al dente”, which was not yet widespread during the early twentieth century except for Southern Italy[11], is another peculiarity of the book. This term defines the emblematic type of pasta’s cooking for which Italy is now famous all over the world[12] and its appearance in the Arte Culinaria seems to hint at its widespread usage among the soldiers.

Today, we still know the names of many dishes in the Arte Culinaria as famous regional recipes like “Pesto alla Genovese”[13], “Pasta alla Madrigiana” [14], and “Cannoli alla Siciliana”. Yet, the listed ingredients point to a different culinary practice which contradicts an idea of a fixated and ahistorical “dish identity”. Today’s food critics would be horrified if they were shown a pesto without pine nuts or a Pasta all’Amatriciana with parsley and marjoram – but precisely such compositions appear in the respective recipes in Arte Culinaria. On the one hand, this fact proves a less dogmatized culinary practice than in today’s Italy – and on the other hand, it hints at another, psychological purpose of the Arte Culinaria.

Beyond Cuisine: The Purpose of Arte Culinaria

However, an inquiry about the grade of precision in which the recipes were reported by the soldiers risks overshadowing the real purpose of this remembrance, as directly stated by Chioni himself in the preface:

Sembrerà naturale come ognuno risognando il domestico focolare abbia ricordato le squisite pietanze e gli intingoli appetitosi preparati dalle mani premurose e delicate della mamma o della sposa lontana; abbia ripensato ai tempi in cui felice presiedeva all’allestimenti di essi e dallo scambio reciproco di ricordi, rimpianti e desideri ne sia scaturito questo ricettario.[15]

It will seem natural that everyone when dreaming of the domestic hearth would have remembered the exquisite dishes and appetizing dips prepared by the caring and delicate hands of the mother or the distant wife; and would have thought back to the times when, gladly, they presided over the set-up of them and that this recipe book was born from the mutual exchange of memories, regrets, and desires.

Chioni writes about a transformation that happened during those months of imprisonment: men turning “da guerrieri in cuochi” [16] – from soldiers to cooks. This had two implications: firstly, in the preface one finds the constant allusion to the presence of men in environments considered to be typically feminine. In Arte culinaria, men and women cohabit the space of the kitchen. But most importantly, the Arte Culinaria underlines both the transformation of the individual and the collective memory in every recipe. In the camp, the memory becomes a tool of positive alienation through which the soldiers can go back to the warmth of their homes, re-experiencing cooking practices. Most of these recipes[17] are nothing but a synesthetic journey of a preparation that comes back to life before their eyes and becomes salvific in organizing survival against food deprivation.

The recipes written down in Celle-Lager provide glimpses of Italian cooking practices beyond Artusi. They become one of those rare cases in which the dietary promise inscribed in the recipe does not fulfill itself in its future making, but in the memories they stir up instead. They contain, even if only from a symbolic point of view, a high nutritive value.

Written by Jamila Converso

Bibliography

Artusi, Pellegrino: La scienza in cucina e l’arte di mangiar bene, Roma 1999.

Bell, David Micheal, Moran, Theresa: Italian Soldiers in WWI and the Emergence of a National Culinary Identity, Dublin 2020.

Caffarena, Fabio: «Da mangiare e immaginare. Il cibo nelle testimonianze di migranti e soldati», in Barbalato, Beatrice (dir.), Autobiographie, convivium, nourriture-Frankenstein, vampirisme, in Mnemosyne o la costruzione del senso, Louvain 2020.

Cavalcanti, Ippolito: (2006), Napoli, Cucina casareccia in dialetto napoletano

Chioni, Giuseppe, Fiorentino, Giosuè: La fame e la memoria. Ricettari dalla Grande Guerra (Cellager 1917-18), Bologna 2008.

Dickie, John: Delizia! – The epic history of Italians and their food, London 2007.

Gadda, Carlo Emilio: Giornale di Guerra e di prigionia, Milano 1999.

ID., Bonaventura, Tecchi (2014), Die Baracke der Dichter: Carlo Emilio Gadda und Bonaventura Tecchi in Celle-Lager 1918. Texte aus der Kriegsgefangenschaft, Klampen 2014.

Montanari, Massimo: Italian Identity in the Kitchen, or Food and the nation, New York 2013.

Spitzer, Leo: Perifrasi del concetto di fame. La lingua segreta dei prigionieri italiani nella Grande guerra, a cura di Claudia CAFFI, Milano 2019.

ID., Lettere di prigionieri di Guerra Italiani, a cura di L. Renzi, Milano 2016.

Footnotes:

[1] At Caporetto (formerly in northern Italy, now in Slovenia) the great Italian defeat by the Austro-Hungarian armies took place in 1917.

[2] The hardship of the camp was also reported by the illustrious Italian writer Carlo Emilio Gadda, in his Giornale di Guerra e di prigionia, Milano, Garzanti, 1999. For an account of Gadda’s experience in Celle-Lager, cfr. Die Baracke der Dichter: Carlo Emilio Gadda und Bonaventura Tecchi in Celle-Lager 1918. Texte aus der Kriegsgefangenschaft, Klampen 2014.

[3] Italian poet and playwright Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863-1938) wrote about the captivated soldiers: “Imboscati d’oltralpe voi non avete diritto di gloria” [“You skulkers from beyond the Alps you have no right to glory!”] thus influencing the public eye, preventing them from getting aid from the Italian government. Cfr. Spitzer (2016), Lettere di prigionieri di Guerra Italiani, a cura di L. RENZI Milano, Il Saggiatore.

[4] Spitzer L. (2019), Perifrasi del concetto di fame. La lingua segreta dei prigionieri italiani nella Grande guerra, a cura di Claudia CAFFI, Milano, Il Saggiatore.

[5] Arte culinaria is not the only recipe collection that came to light in Celle-Lager; in fact, a more fragmented one was written by Giosuè Fiorentino, i. e. B 98 (2008), La fame e la memoria, ricettari dalla Grande Guerra (Celle Lager 1917-18), Bologna, Agorà Libreria Editrice, pp. 119-172.

[6] Luigi Marrazza results as a second lieutenant in ibid, page 3. His biography is difficult to reconstruct, even more than Chioni’s. About Chioni we know that he was captured on October 26th, 1917 and placed in the C-Block.

[7] La Scienza in Cucina is a representative book of Italian cuisine by the end of the 19th century written by Pellegrino Artusi.

[8] Unfortunately, this chapter is incomplete for the loss of one page.

[9] For the most part of the 20th century it was the most consulted cookbook by Italian families for domestic purposes. From its second edition on, it was updated by collecting recipes which the author received by letter sent by the readers themselves up until its 15th edition in 1911.

[10] “Culunganes” is the wrong transcription of a typical Sardinian dish “Culurgiones”.

[11] It is difficult to trace back the expression “al dente” to its origins. However, this practice is testified in a relatively ancient book written by Ippolito Cavalcanti in 1839 know as Cucina casareccia in dialetto napoletano. Here Cavalcanti uses the expression “vierdi vierdi” (this expression aims at reproducing metaphorically the hard texture of unripe fruits) referred to a particular type of pasta, the Stivaletti.

[12] In 1984 “al dente” is listed in the Larousse Gastronomique.

[13] For an historical account of Pesto alla Genovese cfr. Dickie J. (2007), Delizia! – The epic history of Italians and their food, Hodder & Stoughton.

[14] “alla Madrigiana” is the incorrect transcription of a typical dish from center Italy called “Amatriciana”.

[15] Chioni G., Fiorentino, G. (2008), La fame e la memoria, ricettari dalla Grande Guerra (Celle Lager 1917-18), Bologna, Agorà Libreria Editrice, p. 3

[16] Ibid.

[17] There is an exception to the vagueness of the recipe measurements, which lets us suspect the presence of a cook in Celle-Lager, ibid. p.32.

Pictures:

* Created in 1917-18. According to Celle Archive the license for this picture is unknown since the ending of the limitation periodt is unpredictable. If new information about ongoing licenses is available the picture will be removed.

Infospalte

Current category:

Aktuelle Kategorie:

More articles of the series:

Weitere Artikel der Reihe:

- Tasting the Past: Introduction

- Mawmenee in the Forme of Cury

A project sponsored by:

Ein Projekt gefördert durch:

Follow us on Twitter:

Folge uns auf Twitter:

Kommentar schreiben